Spoilers for I, the Executioner (1968). Trigger warnings for discussions of sexual assault.

Doing my research into this film before writing this piece – with much of the credit having to go to Tony Rayns’ excellent essay included in the Blu-ray release from Radiance Films – I discovered that Tai Katô primarily worked as a director for hire, despite being related to Yamanaka Sadeo and working under the legendary Akira Kurosawa on Rashōmon (1950).

This meant that the stories that Katô wanted to tell often had to fit within a desired structure and genre, capitalising on whatever was profitable at the time. His script work would often go uncredited, only noticeable through the themes integrated into the story, and his directorial work between 1963 and 1981 has largely gone unrecognised.

In I, the Executioner, this balance between what the studio wanted and the story that Katô wanted to tell is on stark display. His work had primarily been samurai or yakuza period dramas up until this point, yet tasked with creating something akin to the pink eiga films that were growing in popularity – short, cheaply made films often containing sexual violence – Katô completes the brief but in a way that makes the audience complicit.

While the film focuses on a serial killer, only one murder is shown in its entirety. The rape and murder of Yasuda Takako (Ranfan Ou) is shocking even by modern standards, taking the suffering of the victim further than audiences would see in the pink eiga films. Katô refuses to pull away at any point, highlighting the terror that a sex crime inflicts on the victim and forcing the audience to question their enjoyment in seeing these crimes played out on screen.

This trauma runs through the plot of the film as more is discovered about the killer and the victims. Katô places misogyny and class structure in his sights, subverting the typical thriller model.

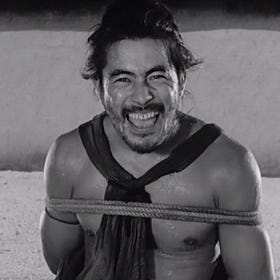

The first way he does this is by revealing the killer in the final moments of that first attack. We know that Iwao Shima (Makoto Satô) is the perpetrator throughout the film, but we do not know why, and Katô is also quick to dismiss any thoughts that Shima may be a monster as we watch him spark up a genuine relationship with the troubled waitress Haruko (Chieko Baishô).

When we find out the motive for the crime, our expectations are subverted once again, changing how we view the killer and the victims. The importance of the victims themselves had already been minimised, as Katô gradually shows less of each attack until the final two victims are killed off-screen. By this point, the audience has been forced to spend such a large part of the running time with Shima, which makes him far more sympathetic when the reveals start.

All the murders stem from the suicide of a 16-year-old delivery boy, who delivered laundry to the five victims while they held a hen party. By the time he arrives, the hen party has grown increasingly raunchy, with the five women watching a porno film. When they see the teenager, they drag him inside and rape him multiple times, the trauma of which drives him to kill himself.

Shima knows about the attack because he knew the teenager, and they bonded because they were both originally from Hokkaido. While never justified, his murders are then thrown in a different light because of this reveal. The assault highlights many imbalances of power. Firstly, all the women are middle class, far above the social standing of the delivery boy. The fact that he was there as a worker further marks him as unequal and this would have made it difficult for him to refuse the coercion of the group.

RASHŌMON

Spoilers for Rashōmon (1950). Trigger warnings for discussion of sexual assault and suicide. One of the first Japanese films to be successfully exported to the West, Rashōmon has become cinematic shorthand for multi-perspective narratives and unreliable characters. Based on the short stories In a Grove and Rash…

Then there’s the question of consent. Society accepts the idea of male consent and male rape when it is a male-on-male crime. When it is a female perpetrator and a male victim, the views on the attack vary wildly. These attitudes are echoed by the victims at various points – both in flashback and in the present – but also by the police officers investigating the case.

These are barely sketched-out characters, designed to add moments of comic relief in a very intense film and to be a soundboard of cultural expectations. Conversations between the two often result in them discussing how they would react if a family member had been attacked like one of the female victims, but when the assault on the delivery boy is brought to light, they laugh off the possibility of a woman raping a man. Going as far as to say that a man would be told by his friends to shut up and enjoy it.

It’s a small but pivotal moment in the film. It comes just after the revelation of what happened at the hen party and so is perfectly timed to mimic the audience’s own response to this. You can imagine men and women in the cinema leaning over to their friends to make a series of crude remarks. Yet the police are so inept that it instantly puts a black mark against holding the same opinion as them.

I, the Executioner cleverly subverts not only the attitudes of the time but also stands out today as a remarkably progressive genre experiment. It isn’t perfect, there are still many of the misogynistic tropes that are prevalent in pink eiga and erotic thrillers, and the plot is further complicated by the fact that Shima is already on the run for murdering his unfaithful wife back in Hokkaido. This added plot wrinkle weakens the case that these crimes are simply revenge for what happened to the delivery boy.

Director: Tai Katô

Writers: Tadashi Hiromi, Tai Katô, Haruhiko Mimura

Starring: Makoto Satô, Chieko Baishô, Sanae Nakahara, Ranfan Ou, Kin Sugai, Junkô Tôda, Yuki Karamura, Tatsuo Matsumura