Spoilers for Rashōmon (1950). Trigger warnings for discussion of sexual assault and suicide.

One of the first Japanese films to be successfully exported to the West, Rashōmon has become cinematic shorthand for multi-perspective narratives and unreliable characters. Based on the short stories In a Grove and Rashōmon by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, it presents witness testimonies of the murder of a samurai (Masayuki Mori) and the assault of his wife (Machiko Kyō).

The different perspectives are recalled by a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) and a priest (Minoru Chiaki), who were both present at the hearing. They tell their stories to a commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) as the three wait for a thunderous storm to finish.

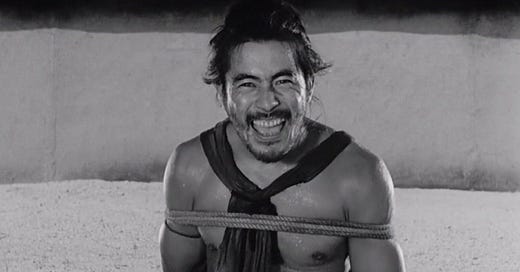

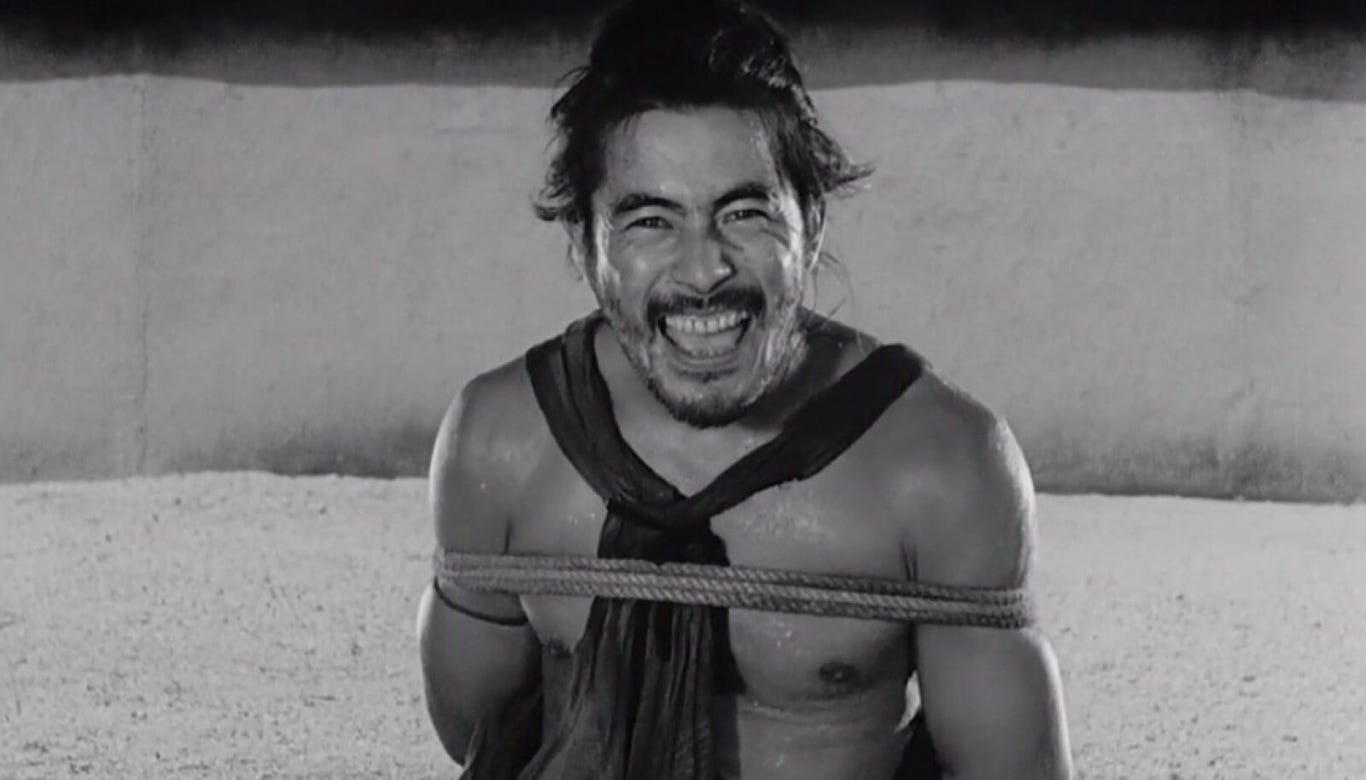

For his direction, Akira Kurosawa looked to silent films. The characterisations are heightened, emphasising one aspect. So, the bandit accused of the crime (Toshiro Mifune) is exaggerated, laughing manically, and running erratically through the flashbacks. The samurai, on the other hand, is stoic, comically so. It’s a neat visual trick, which would have helped Western audiences overcome, in the words of Bong Joon Ho, “the one-inch barrier of subtitles.”

Much of the film is taken up with three variants of events. We see the bandit’s testimony, in which he exaggerates his cleverness and wickedness, as well as suggesting that he, in some ways, won the girl afterwards. Regardless of the truth of events, he remains guilty of at least one crime and so looks to increase his legend before being sentenced to death.

The wife’s story is morally grey, stating that she was assaulted but that the bandit did not kill her husband. Instead, the husband was contemptuous towards her, her honour lost after the rape and was either killed by her when she blacked out or committed seppuku while she was unconscious.

Through a medium (Noriko Honma), the samurai gives his version of events. Showing the bandit to be genuine in his declarations of love for the wife, and cowardly when it comes to the prospect of fighting the samurai. Like most versions of the truth, it is a middle ground between the previous events and the one we assume is accepted by the court.

However, Kurosawa’s visual storytelling is also at its best here. Throughout the testimonies, the woodcutter can be seen in the background. At first, it’s a strange choice; sat slightly off-centre, his presence feels out of place in what would be clean shots of the primary protagonists. However, during the medium’s retellings, his presence becomes important.

The end of the samurai’s retelling reveals that after committing seppuku he felt someone remove the dagger from his chest. Until this point, the dagger has been primarily used as evidence that the wife fought the bandit. That she did not willingly give herself to him, heightening the drama between her and her husband, and satirising the archaic ideas of honour.

However, the woodcutter reacts strongly to the implication that the dagger was stolen. While the medium remains front and centre, Honma dials back her performance for a moment, drawing the audience to Shimura’s excellent facial expressions.

While the film continues to show a fourth version of events, the implications in these few seconds of film get the moral heart of Rashōmon. In the eyes of the law at the time – the film is set in the Heian era, between 794 and 1185 – the samurai, the wife and the bandit have committed some sort of transgression. Yet, the different testimonies provide justifications, and it is up to the audience to decide who is in the right. Kurosawa gives no easy answers here.

Similarly, at the end of the film, we see the woodcutter take the moral high ground over the commoner. Even without the explanation of him stealing the knife so that he can sell it to provide food for his family, the few glimpses of the woodcutter’s facial expressions are enough to indicate that even the witnesses are not completely innocent in this chain of events.

The commoner leaves the priest and the woodcutter, explaining that everyone – man and woman – is driven by their self-interests. This is writ large in Rashōmon, yet Kurosawa is not so unambiguous as to place judgement on the characters. We all have our morally grey sides, certain things we will do for self-preservation and lines we will not cross.

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Writers: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto. Based on the short stories In a Grove and Rashōmon by Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Starring: Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, Takashi Shimura, Minoru Chiaki