Spoilers for Trans-Europ-Express (1966). Triggers warnings for discussions of sexual assault.

In his most playful combination of eroticism and experimentation, Alain Robbe-Grillet explores the creation of art and what happens when it’s released into the world. In his 1963 collection of writings, Pour un nouveau roman, he argued that traditional novels create the illusion of order.

For Trans-Europ-Express, his second feature and the first collaboration with leading man Jean-Louis Trintignant, he invites the audience into a collaboration as Robbe-Grillet, his wife Catherine and Jérôme Lindon sit on the titular train and create a story about a drug trafficker using the international service.

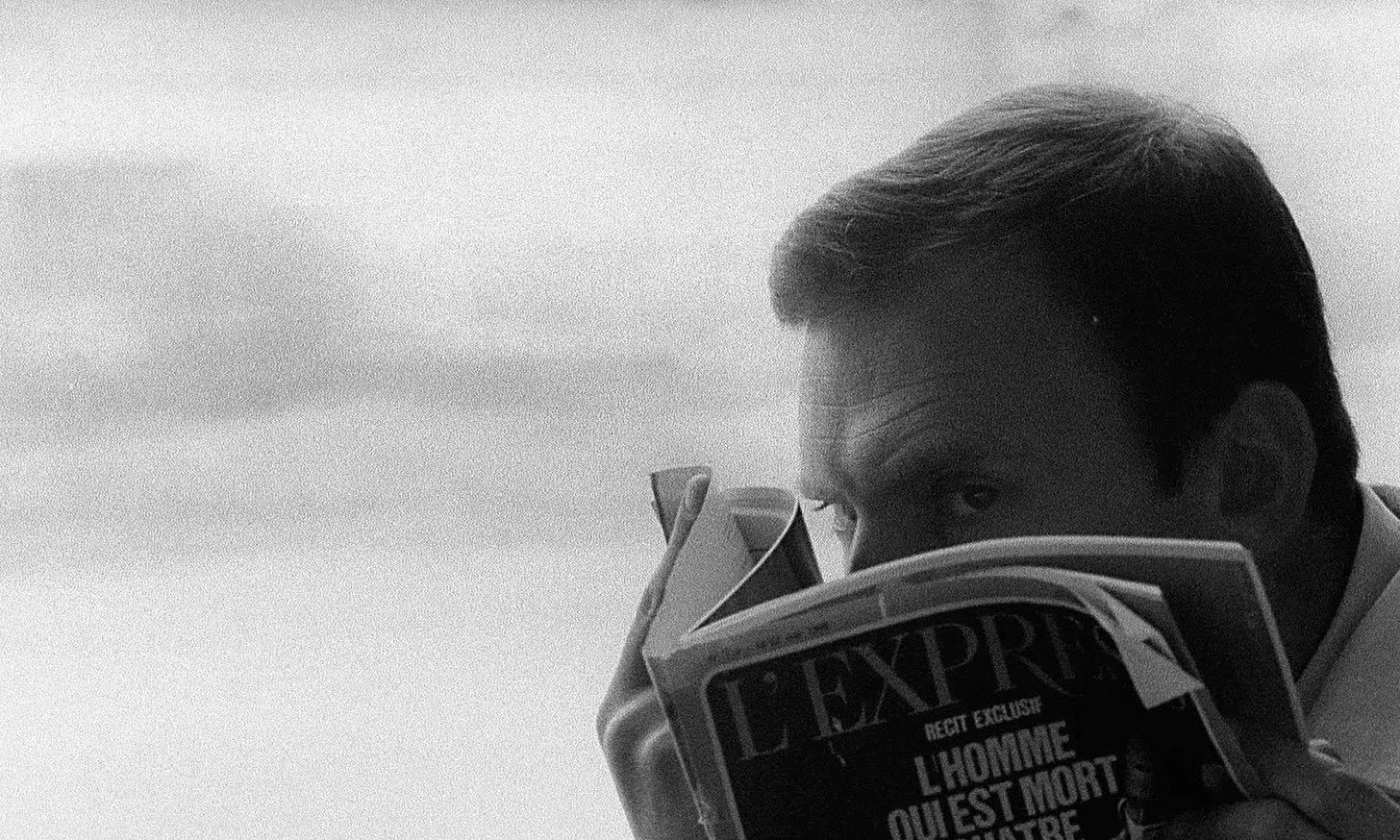

At this point, we are introduced to Elias (Trintignant), who is charged with transporting drugs from Paris to Antwerp. As well as bumping into the filmmakers in their carriage – who recognise him as the actor, rather than his character – he does his best to hide a sadomasochistic pornographic magazine in his newspaper and flirts with a young woman, who may or may not be a member of a rival trafficking group.

Catherine, playing the script continuity girl, does her best to talk Alain out of using a rival gang member, and so the film cuts, and rewinds. Already, we see how the finished product starts to evolve from the messy notes put together at the start. In an interview with Catherine Robbe-Grillet, included on the BFI release of this film, she says that Alain saw the script supervisor as someone to bounce the film against. His various ideas challenge continuity, as the audience struggles to keep pace.

Forced to run between multiple arbitrary points before he gets hold of the drugs, Elias starts an affair with a prostitute, Eva (Marie-France Pisier), with whom he enacts a series of rape fantasies. However, it’s clear that the story is not moving as Alain wants, and the character of Elias seems to grow resentful of even being in the story.

We see this early on when Elias buys the magazine at the train station. He looks back at the camera, and shuffles to try and block our view as he slips the porno mag into the newspaper. In Catherine’s introduction to the film, she says that while Alain was more subtle with his humour, it was the relationship with the leading man Jean-Louis that brought out this more overt comedy in the film.

His drole exchange with Eva highlights this:

Eva: And you? What do you do for a living?

Elias: I'm an assassin.

Eva: Professional?

Elias: No, amateur... semi-professional, actually.

In fact, you could make the argument that Trintignant isn’t playing a role for the director. This is closer to a stage performance, something that is aware of its audience and is strategically exaggerated. When Alain describes the film he wants to make at the start, he says that he wants to create something ‘full of rape and violence’; something that is exciting.

No surprise then, that the various sequences feel staged. The sexual encounters between Elias and Eva feel stilted as if they are being directed on the spot. A scene introduced purely for titillation. Similarly, the script supervisor points out that having Elias run between various middlemen, only to be pointed in the direction of another middleman, does little but artificially raise the stakes.

What the audience gets is a rough draft of a film, which becomes complete because of the interactions. Trans-Europ-Express treats us like beta readers, only the various issues are solved in front of us. It continues Alain’s interest in subverting genres. His 1955 novel, The Voyeur (Le Voyeur), is a murder mystery without the murder. We are never sure if the killing has happened, is about to happen, or is simply a fantasy.

Here, we watch the creation of a film about a drug deal, only for the drug deal to be a practice run – one that creates an unnecessary escalation in danger simply to add further excitement at the climax. Made in the decade before auteurism started to bankrupt studios, Alain creates a dynamic with the script supervisor that keeps him on track.

But it also acts as a comment on the ownership of art. Once a piece of work is released, the audience takes ownership of it. They explore themes and overlay their feelings on them. This very newsletter is built around looking at themes (both intentional and unintentional) that grab our attention.

Trans-Europ-Express explores this by suggesting that the artist never really has control of their vision anyway. Alain loses control of Elias at the start, and when we cut back to the filmmakers, they are trying desperately to pull the story back in line. How many writers have said that the characters eventually take control of the story? That the writer only has control over the initial outline. For filmmaking, even more factors must be considered, including the financials – it’s likely no surprise that the producer is also in the carriage.

And the final scene, when the filmmakers get off the train and we see Elias (who we had presumed was dead) and Eva (who has also passed in the film) embrace in the background, it suggests that they have fully lost control of the film. Now that the story is out into the world, the audience can create alternative realities for these characters.

Writer/director: Alain Robbe-Grillet

Starring: Jean-Louis Trintignant, Marie-France Pisier