Spoilers for The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Note: We used the 135-minute 1976 original cut, rather than the 108-minute 1978 cut.

There’s a cruel irony that The Killing of a Chinese Bookie would be one of John Cassavetes’ least commercially successful films. Having written and directed fiercely independent films since the late 1950s, funded by his acting work, Cassavetes looked to the booming gangster films as a way to break into the mainstream and procure funding for later projects.

But while the film exists in the same seedy world as Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), Cassavetes was unable to capture that same widespread appeal. In truth, he was critical of the genre and its glorification of criminality, so the various plot points we would expect are told in a more downbeat and naturalistic style.

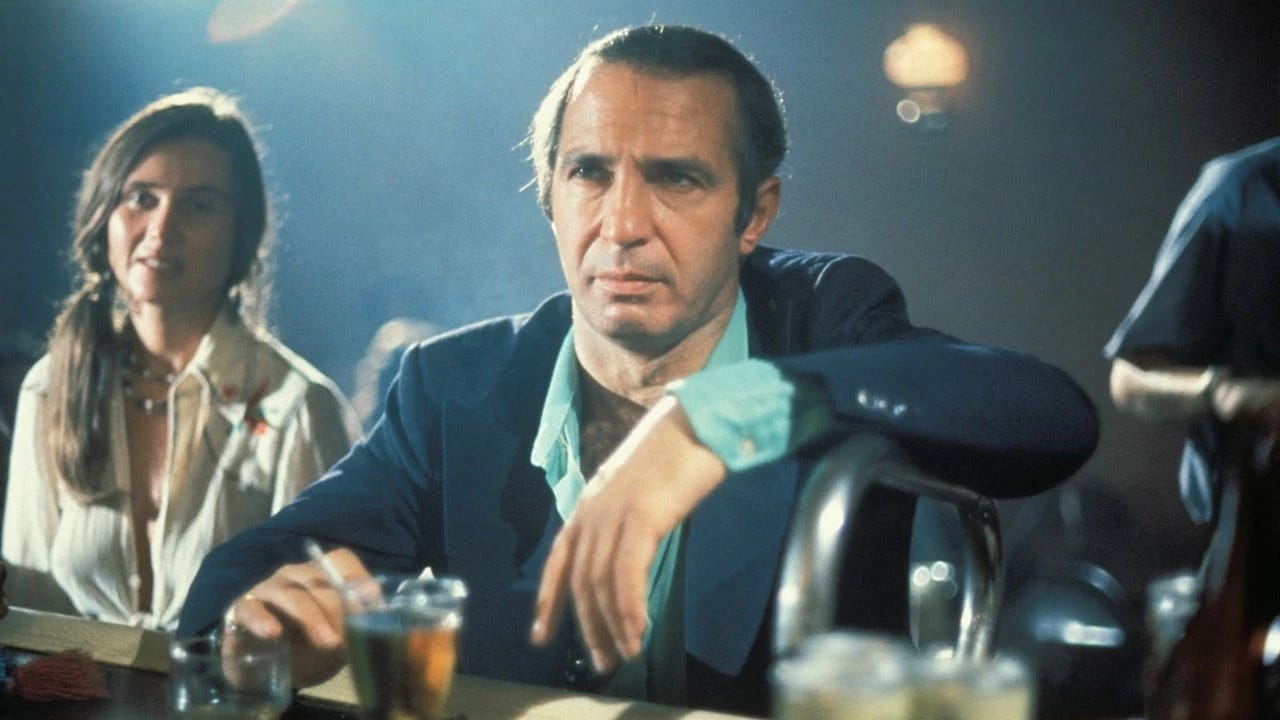

Regular Cassavetes collaborator Ben Gazzara plays Cosmo Vittelli; a club owner with dreams of glamour and a gambling addiction that constantly pulls him back down. At the very start of the film, we see him make the final payment to a loan shark (played by producer Al Ruban) and he celebrates on the way back to his club. His high is short-lived though when Mort Weil (Seymour Cassel) approaches him and tells him about a club, Ships Ahoy, where poker games are played in the back.

We’re very quickly aware that the game, Cosmo’s debt, and the subsequent events are a set-up. Mort, along with his partners, wants Cosmo’s club, and our protagonist accrues $23,000 of debt, he is put in a position that will likely get him killed. To pay off the remainder, Mort says that Cosmo must murder a bookie named Harold Ling (Soto Joe Hugh). Harold, however, is a high-level Triad boss named Benny Wu, and Cosmo’s creditors expect him to be killed during the assassination.

While the machinations are in place, the film never follows the straight and true direction. We follow Cosmo through the streets and in the backrooms of his club, when the inevitable killings do come, they are often off-camera, with Cassavetes focusing on the gun or the perpetrator. Characters are nearly always filmed in close-up, highlighting where Cassavetes’ interests truly lie.

The film becomes an account of the director’s troubles, with Cosmo being a stand-in for Cassavetes. We can see this in the way that Cosmo runs the Crazy Horse West. It’s a strip club, but Cosmo choreographs more artistic burlesque acts, led by the quirky Mr Sophistication (Meade Roberts). He sees himself as an entertainer, offering something a little less seedy than other competitors, yet his clientele is often only there for the girls.

You can see the parallels with the production, where Cassavetes tries to give audiences the sort of film they want but his artistic direction skews the genre. The camera constantly focuses on the wrong part of the frame, missing the violence and the bloodshed. Cosmo believes that the Crazy Horse West will reach the fame of the classic Parisian clubs; Cassavetes believes The Killing of a Chinese Bookie will bring an end to the grind of finding funding and creating critically acclaimed but commercially ignored films.

In both cases, money is the issue. It’s not a stretch to compare the gangsters that force Cosmo into this scenario to the film industry. There’s no leniency when money is owed. When the final betrayal is put in place, Cosmo is driven to a parking garage by one of Mort’s associates, Flo (Timothy Carey). Flo says that he considers Cosmo a friend and expresses regret about what is going to happen, but it is just business.

“That jerk Karl Marx said opium was the... religion of people. I got news for him, it's money.”

Like Cosmo, Cassavetes feels like the only way to escape his circumstances is to constantly gamble on the next big thing. But fitting into the next big thing would result in making a film that he is unwilling, or unable to make. A film that would shift the focus from his carefully drawn-out characters and the improvisational dialogue to something more bombastic.

As we reach the end of the film, an injured Cosmo addresses Mr Sophistication and the girls at the club. He tries to stay light-hearted but eventually admits:

“Look at me, right? I'm only happy when I'm angry... when I'm sad, when I can play the fool... when I can be what people want me to be rather than be myself.”

It’s hard not to think of Cassavetes’ acting work when he says this. He was a towering presence on the screen, taking roles in The Dirty Dozen (1967, Robert Aldritch) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968, Roman Polanski) and using the money he received to fund his pictures. As an actor, he was a critical success and commercially recognisable, if not entirely bankable. The world accepted Cassavetes as an actor but often rejected his directorial efforts. Even his most revered works, Husbands (1970) and A Woman Under the Influence (1974), were critically applauded but struggled to make a dent in the box office.

When Cosmo says he is only happy when he is what other people want, it’s hard not to think of Cassavetes’ disappointment with his directorial career; held back by his individualism, which stood out even during the auteur movement, and fickle audience numbers.

Writer/director: John Cassavetes

Starring: Ben Gazzara, Timothy Carey, Seymour Cassel, Morgan Woodward, Azizi Johari