Spoilers for Quälen (1983)

Prolific British filmmaker Michael J Murphy was widely unappreciated until Powerhouse Films released a comprehensive collection of his films, however over the course of nearly 50 years he created an unbelievable amount of microbudget shorts and features, primarily in the fantasy and horror genres.

Quälen, released in the USA as The Hereafter, is a remake of his 1976 Secrets, with the genders of the main characters swapped. Notably, this version of the story also takes some gory cues from Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood (1971). Part of the joy of Murphy’s filmography is how he would stretch his miniscule budgets, using a familiar cast of friends and locals, and drip-feeding the scares so as not to push the practical effects.

For the uninitiated, this can make Quälen a difficult watch. Even with the excellent remastering from Powerhouse, this doesn’t look amazing. All of Murphy’s films were shot on 8mm and 16mm, but the original elements of Quälen have been lost to time. This remaster was done using standard-definition analogue elements, so even dragged up to 2k, there’s plenty of grain obscuring things. Then there’s the performances, which are often stilted, and often verging on unintentionally funny.

But that’s part of the joy of Murphy’s films. Despite the limitations, he clearly understood the process of making a quality film and beyond the surface-level complaints, nearly everything in Quälen (dodgy karate sequence near the beginning notwithstanding) can stand against a lot of the horror films made around this time. Even the performances often add to the experience, creating a dry, very British sort of humour throughout.

Neville Harmer (Steven Longhurst) is the downtrodden son of wealthy sawmill owner Alfred (Al Greer). Confined to a wheelchair, Alfred has become bitter and berates Neville at every opportunity, as well as Neville’s girlfriend Vicky (Caroline Aylward, credited as Catherine Rowlands). When walking the grounds one day, the pair get into an argument and Neville storms away, only for the brakes on Alfred’s wheelchair to mysteriously fail and send the cantankerous old man over a cliff face and into the lake below.

Set to inherit the estate and the sawmill, Neville has mixed feelings about events, only to have reality come crashing back down at the will reading when he discovers that he and Vicky will have to live at the estate, instead of selling it, or the property will be split between all the surviving relatives.

At this point, we start to get to the crux of the story. Neville explains to Vicky that the estate is haunted. The spectre in question won’t let anyone leave the house, at least not unless they’re in the confines of a casket. Murphy quickly moves away from this idea though, instead turning the film into a thriller of sorts, as Neville is himself paralyzed when Vicky’s lover Patrick (Colin Efford, credited as David Slater) attempts to kill him, leading to the estranged lovers playing a psychological game of cat and mouse.

We see a lot of Murphy’s character work in the latter part of the film, as he realistically plots Neville’s transformation into his father. Turning from a put-upon, angry young man, into someone far more embittered and unable to influence the events around him. It suggests that what happens in the house is less a haunting, and more of a curse, inflicting misery on the inhabitants.

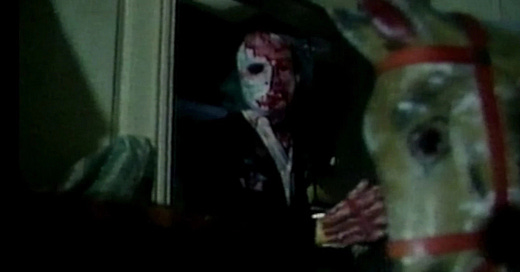

But while the development of Neville becomes a highlight in the later stages of the film, my favourite parts of the film highlight Murphy’s ability to create horror within the confines of the budget. In this, the disfigured monster that attacks Neville is a genuinely creepy addition – until we later find out it was Patrick. Part of this is the mask that the attacker wears, which through the film grain becomes an uncanny, distorted nightmare.

We can see something like a face, but it’s certainly not a face we’d like to encounter.

The attack is a well-paced affair, as Neville is chased around the upstairs of the house. The fact that none of the actors were trained in stunt work, makes some of the movements ungainly, akin to when Leatherface would hunt down a victim in the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974).

Even earlier in the film, during Vicky’s birthday party, Neville heads down into the basement to collect more wine. As he leaves, he hears the knock of his father’s cane against the wall and looks back into the wine cellar to see Alfred’s wheelchair appear out of the darkness. Again, it’s a moment where the budget restraints benefit the film. The cellar is nearly pitch black, meaning the audience is straining to see what Neville is seeing. We only get the slightest glimpse of the wheelchair, along with a pair of monstrous, swollen hands.

These highlights might seem small, but they build a picture of a director who had all the talent required but lacked some of the tools to make an impact. The variety within his filmography and his ability to go back and draw from earlier films show improvement over the decades.

We often say that anyone can be a filmmaker today, with high-definition cameras in their pockets. Michael J. Murphy is proof that this is not the case. The truth is that for as long as we’ve had cinema, we’ve had the tools for anyone to be a filmmaker. Mass-market film cameras were available from the early-1900s, and Kodak introduced low-cost, 16mm film in the 1920s. While these would have initially been the playthings of the rich, like all technology, the price soon dropped to make it available to families.

Murphy is proof that anyone can make a film, but not everyone can be a filmmaker. Through his filmography, we see an artist who truly understood his craft, and everything in Quälen, from the character development to the sparsely used scares, is a testament to this.

Writer/Director: Michael J. Murphy (credited as Michael Melsack)

Starring: Steven Longhurst, Caroline Aylward, Colin Efford, Wendy Young, Yvette Guntar, Al Greer