Spoilers for Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975). Trigger warnings for discussions of suicide

Peter Weir’s dreamy adaption of Joan Lindsay’s classic novel offers little in the way of answers, but is heavy on subtext. On the surface, the film is a supernatural mystery, following the disappearance of three school girls, and one of their tutors, at Hanging Rock but following the lead of the source novel, Weir (alongside screenwriter Cliff Green) brings to life the damage of colonialism and repression.

Throughout the film, the lives of Australians are shown to be controlled by the English, a cultural eradication not through violence, but through a slow erasure of lifestyles and culture. If we ignore the excised final chapter from Lindsay’s novel, which suggested the existence of a time loop, Hanging Rock could be seen as a physical manifestation of how the Australian outback is seen from the outside – wild, unnerving and unforgiving.

More interesting is the idea that Hanging Rock has reclaimed these girls. These are Australian nationals being educated and controlled by an English governess. As such, the values that they are brought up with are ‘traditional’. Not only does the Australian culture get overwritten by a distinctly European one, but the various desires of the young women are repressed. Hanging Rock is heritage and history, but it is also the wild freedom of nature. A place where time seemingly stops and our baser instincts take over.

In evidence of this, when four of the students initially start their ascent of the Rock, they begin to shed their restrictive clothes. They take off their shoes and stockings, putting them in direct contact with the ground – with Australia. While not on screen, their mathematics teacher Mrs McCraw (Vivean Gray) is witnessed shedding her clothes as she makes her own way up the Rock.

Whatever happens to these women as they disappear on the Rock, it is an escape from the repression and cultural erasure they have undergone. The three students who go missing are not scared, or unnerved by the rock, instead they willingly follow the unknown force that guides them. There is of course a quirk to this, Edith (Christine Schuler), who follows her classmates to the summit of Hanging Rock but does not enter the crevice where they disappear. Nor does she seem impacted by the forces at work.

Yet Edith herself is more effected by the natural Australian climate. She suffers in the heat; she tries to fit in with her classmates but both mocks them and moans about the climb. In many ways, she rejects her own culture, striving to fit in but to fit in away from the stifling heat of the outback.

While the fates of the women at Hanging Rock are steeped in subtext, things are far more literal when it comes to the fate of Sara (Margaret Nelson). Sara is an orphan, refused permission to go to Hanging Rock and instead forced to learn poetry by the governess Mrs Appleyard (Rachel Roberts). It’s clear from the beginning of the film that Sara has feelings for one of the other girls, Miranda (Anne-Louise Lambert), something completely out of step with the traditional values taught at the school.

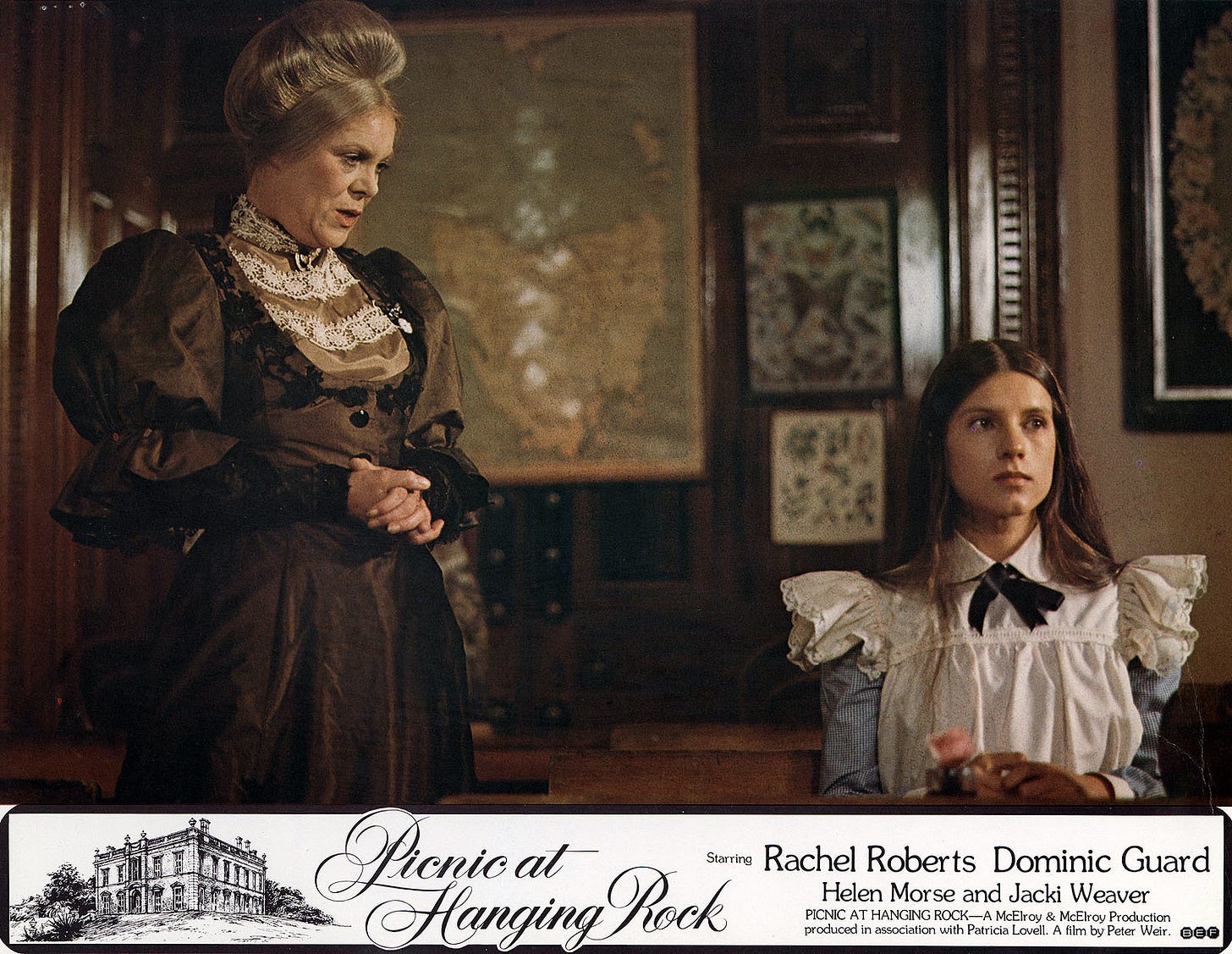

As a director Weir, following the lead from Lindsay’s novel, refuses to be overt about many things in the film. However, the scene between Mrs Appleyard and Sara is rather blatant, though no less beautifully shot or scripted. Sara cannot learn her poetry assignment – Felicia Hemans.

Appleyard, disbelieving that Sara would be unable to learn Hemans (“…one of our finest English poets…”), despite the fact that she confuses the poet with another, threatens the girl with punishments but Sara stands her ground, offering to recite a different poem.

The poem – An Ode to Saint Valentine – was written by Sara for Miranda. It simultaneously represents Australian culture, being written by Sara, and a non-traditional relationship that would be looked down upon not only by the English overseers but, due to this being set in 1900, likely by most of the world.

Rather than hear Sara out and allow her to recite her own work, Mrs Appleyard dismisses her out of hand.

“Strange as it may seem, I prefer Mrs Hemans.”

As an ex-patriate, Mrs Appleyard imposes her English preferences and values on the girls, and lashes out at them when they show any individualism. This basic view of colonialism, stripped of much the brutality that has been used throughout history, informs the unsettling atmosphere that permeates the film. By the end, all but the women who disappeared in the crevice at Hanging Rock are portrayed as strangers to the place where they live.

Sara’s tragic story, which culminates in her seemingly jumping out of her dorm window (or being pushed by the increasingly unhinged Mrs Appleyard) is made worse by the fact that she was kept from Hanging Rock. Like the classmates who disappeared, she is perhaps the most comfortable with herself, with her heritage and with the vast open space around her.

Her ’Ode…’, dismissed out of hand, is a cultural backlash against her oppression; a fight which nature finishes by the end of the film.

Director: Peter Weir

Writer: Cliff Green. Based on the novel of the same name by Joan Lindsay

Starring: Rachel Roberts, Anne-Louise Lambert, Margaret Nelson