Spoilers for King of New York (1990)

The 1990 neo-noir King of New York is not a perfect film. Its pacing is choppy, its storyline contains too many players for them all to be satisfactorily rounded out. In many ways, it is style over substance – a collection of thrilling set-pieces that position organised crime, law enforcement and the political backbone of the Big Apple as one and the same.

Abel Ferrara’s films have always veered towards horror, even when grounded in very real situations. King of New York is no different. People don’t die quickly in this film; it’s visceral and bloody. They cry out in pain or run away in fear. Despite not sitting comfortably in the genre, King of New York is one of the director’s more overt horror films. It’s brutal violence and grim world are one thing, but a scene halfway through highlights the mythic influences behind the main character.

In a bid to broker a deal between Frank White (Christopher Walken) and the Triads, Joey Dalesio (Paul Calderon) meets Larry Wong (Joey Chin) in a cinema. While they discuss a major drug sale, F. W. Murnau’s 1922 classic Nosferatu plays on the screen.

At first glance, this has no wider implications. Nosferatu has been out of copyright protection for decades and is often used in films to avoid paying fees to production companies. On closer inspection, however, you can see the vampire mythos throughout the entire film, especially in the lead performance of Walken.

Frank White is a drug lord who has just been released from prison and who aims to take over all the operations in New York. He then plans to use this power to legitimise his business interests. Walken gives a stoic, menacing performance, often in stark contrast with the rest of the actors. Compare him with his hyperactive, trigger-happy right-hand-man Jimmy Jump (Lawrence Fishburne) and Frank is practically statuesque.

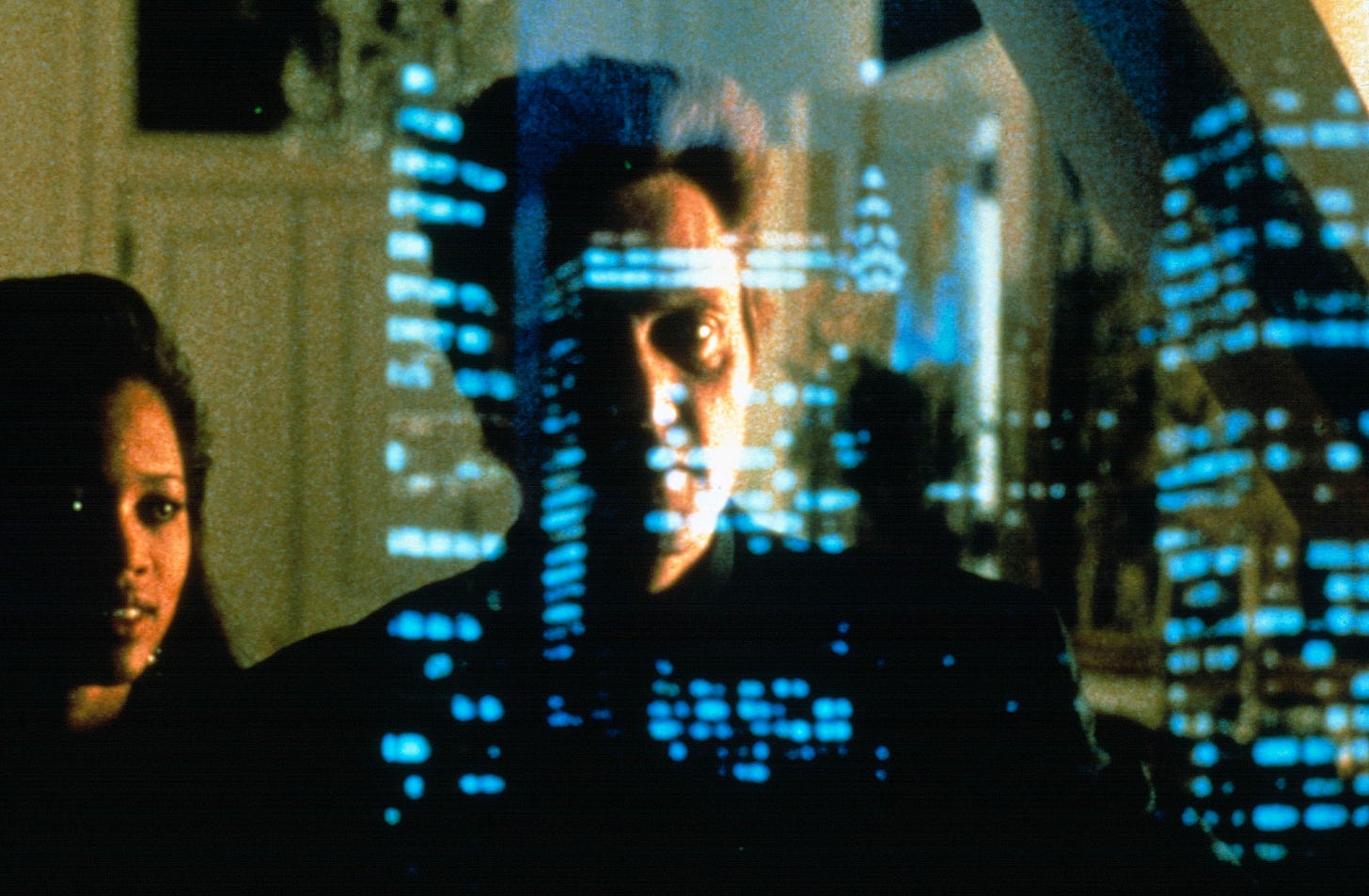

He’s hardly the monstrous figure portrayed in Nosferatu, but he shares many of the features of Dracula. He is a charismatic businessman; drawing people into his web and using them to act for him, never resorting to violence himself unless he is forced to. His presence is often enough to change the atmosphere of the scene. He speaks softly and deliberately, never breaking eye contact with the other person. In crowd scenes, he moves in the background, often in the shadow and whispering in someone’s ear.

When he does move, it’s quick and graceful. Walken uses his dancing experience to make Frank glide across the screen. Perhaps the most famous example of this is when he reconnects with his crew after his release. Stood in a penthouse, overlooking the city, he stares down the crew (who have been working on his behalf to take out rival gangs) before busting out a series of rock ‘n’ roll dance moves. His switch is so fluid, and over as quickly as it began. It is Dracula dancing around Lucy Harker.

Like a vampire, Frank is only seen at night. In fact, only a handful of scenes in the whole film take place during the day, and only two involve Frank. One is the sudden, brutal assassination of policeman Dennis Gilley (David Caruso), where Frank appears in a blacked-out car and only opens the window to deliver a fatal shotgun blast. From a storyline perspective, the blacked-out windows serve to hide his identity, but it adds to this idea that Frank White is a creature of the night.

Ferrara does not make Frank White out to be a literal vampire, instead, he compares the underworld to vampires. On every level, these crimes suck the life out of people. Whether it’s selling drugs directly to addicts or manipulating the legislative workings of the city for personal gain. Frank wants to legitimise his business interests but remain in control of the drug trade. His machinations with politicians are like Dracula’s attempts to buy property in the UK – legitimate fronts for horrific crimes.

As always, there is a small group working to take down the villain. The film does not have a direct parallel to Dracula’s famous hunter Van Helsing; instead, its three intrepid police officers. Dennis Gilley, his partner Thomas Flanigan (Wesley Snipes) and their boss Roy Bishop (Victor Argo) know the danger that Frank represents. In vampire myths, the heroes are often dismissed, and their theories are played off as fantasy. Here, corruption hampers their attempts to bring down Frank and they are forced to fight fire with fire.

Perhaps the most telling link between Frank and vampirism comes at the very end of the film. The second time we see Frank in daylight. With his crew dead and his plans falling apart, Frank is forced into an open battle with a vengeful Roy. Roy is killed in a shootout in the subway, and while Frank walks away, he too is mortally wounded.

Notably, he’s killed by a shot to the chest. Admittedly to the right-hand side but close enough to resemble a stake through the heart. Frank dies in the back of a car, in New York traffic, as the sun rises. Like Nosferatu, the sun is anathema to Frank. His sins can’t survive exposure to the light. Without the darkness to hide in, he’s weak.

Director: Abel Ferrara

Writer: Nicholas St. John

Starring: Christopher Walken, Lawrence Fishburne, David Caruso, Wesley Snipes, Victor Argo