Spoilers for Battle Royale (2000). Trigger warnings for brief descriptions of suicide and child abuse

The final completed film of legendary director Kinji Fukasaku before his death from prostate cancer three years later, Battle Royale has gone on to be one of the most influential films. It has inspired genres that cross modes of entertainment, from films and television to video games.

It’s based on the novel of the same name by Koushun Takami, which was completed in 1996 but not published until 1999. The novel was controversial upon release, wrapping the central plot of high schoolers being forced to kill each other within a fascist Japanese society that prioritises military strength and survival skills.

Fukasaku (working from a script written by his son Kenta) changes this. Instead of a fascist government, we are plunged into a world where recession has stripped Japan’s youth of future opportunities. Disenfranchised, they lash out, with juvenile crime soaring across the country. To exert control over the younger generations, the government creates the Battle Royale Act, where a high school class is randomly chosen and transported to an island to kill each other.

It's a shrewd change. While Takami imagined a military dystopia, Fukasaku creates something that older viewers would probably have believed was already happening. Distrust and dislike between generations are common. Unfortunately, we seem hardwired to find fault with the people who follow in our footsteps. While no one is suggesting that Millennials or Gen Z should be forced to murder each other on an island, our rhetoric places blame on younger people who are trying to make their way through a world that previous generations have had the opportunity to shape.

It's a no-win situation. The youth are punished by the actions of those who came before, and then punished for rebelling against it.

Regardless of the horrors on screen, Fukasaku never allows the audience to forget that these characters are just children. They are 15 years old when they are suddenly forced to kill their classmates – a group of teenagers, chosen at random to be punished for the sins of others.

This focus on their youth and innocence, and consequently how easy it is to destroy, is clear from the opening moments. We see the final moments of the previous Battle Royale, with journalists trying to push past the military to get a closer look at the winner. When we see her (Ai Iwamura), it’s a purposefully childlike image. She holds a stuffed toy close to her chest but when she looks up, she smiles. Smiles because she survived. Smiles because she killed so many – an offhand comment suggests that this round was particularly brutal. The blood splatter and the smile pervert what would otherwise be a rather typical image of childhood.

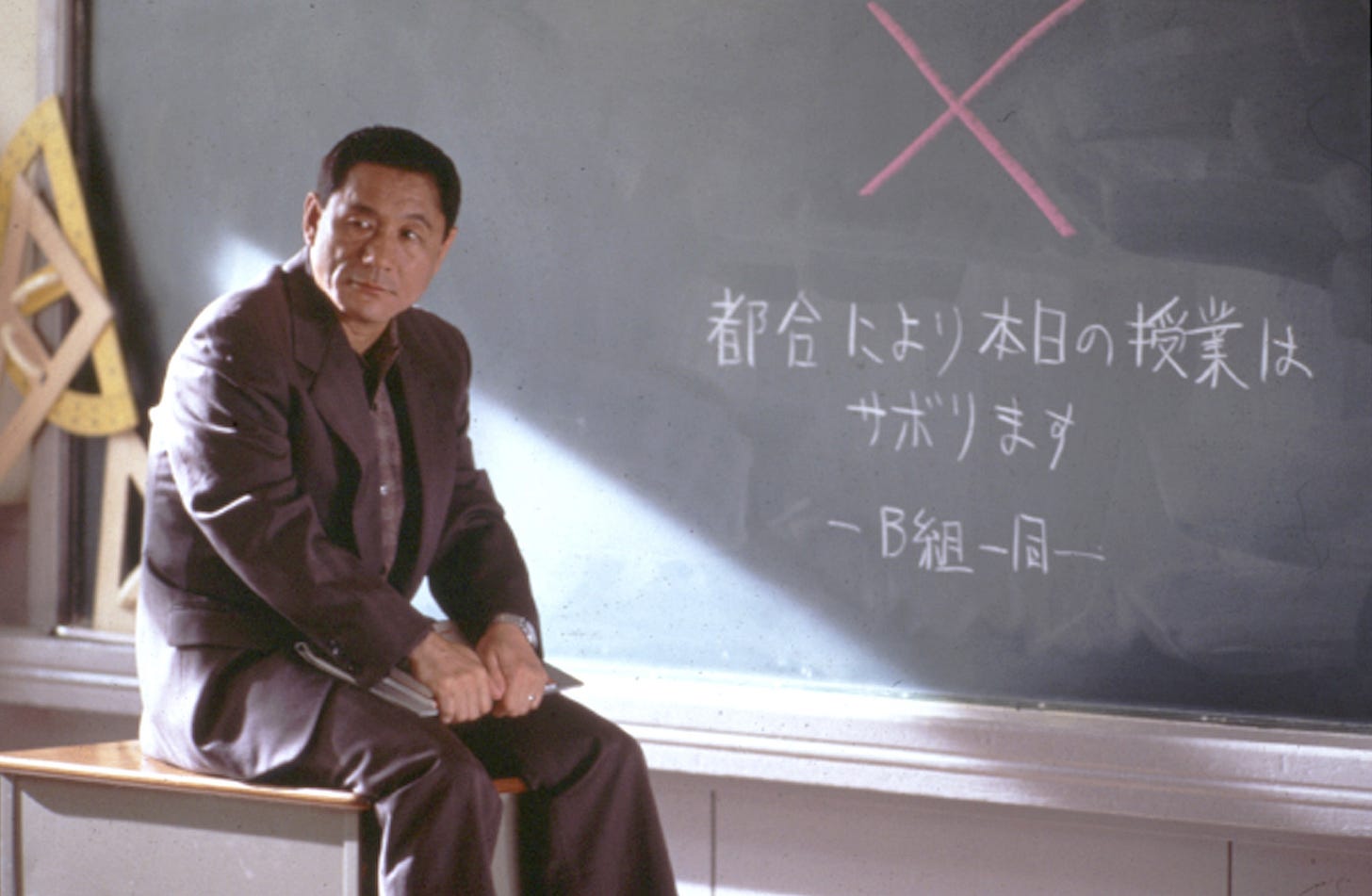

Cut to Battle Royale depicted in the film and the flashbacks indicate that many of these teenagers are not the delinquents that the government has suggested. One of the earliest victims, Yoshitoki Kuninobu (Yukihiro Kotani) stabbed his teacher Kitano (Takeshi Kitano), but the film makes it clear that this child – living in a foster home – is troubled.

Our protagonist, Shuya Nanahara (Tatsuya Fujiwara), is struggling to process the suicide of his father, while one of the most violent in the class Mitsuko Souma (Kou Shibasaki) is shown to have survived an abusive household.

Most of the others (barring the volunteer participant and the student forced to come back) are shown to be normal kids. They play sports; hang out and listen to music. They develop young relationships that feel all-encompassing. One of the film’s strengths is its ability to show a very relatable childhood between the moments of horror.

As each of the students are killed off, there are moments when disbelief takes over. At the start, some still believe Battle Royale to be fake somehow. There is a genuine shock when a crossbow goes off and kills another student. Or when one of their peers throws themselves into the ‘game’ in a bid for survival.

Even when more than half of the class has been murdered, some struggle to comprehend what is going on. This is perhaps best represented in the lighthouse scene. Shuya has been rescued and nursed by five girls. One of these, Yuko Sakaki (Hitomi Hyuuga), witnessed Shuya accidentally kill Tatsumichi Oki (Gouki Nishimura) and plans to kill him by mixing cyanide into his food.

The other girls are unaware of her plan and discuss joining Shuya, who is working with Noriko Nakagawa (Aki Maeda) and Shogo Kawada (Tarō Yamamoto) to escape the island. But when Yuko mixes the poison in, the bowl is taken by Yuka Nakagawa (Satomi Hanamura), who subsequently dies. This throws the remaining girls into paranoia, as they all point fingers at each other. Ironically, Yuko’s quiet and nervous persona means that she is the only one not suspected of the killing.

They each grab guns while Yuko hides. Satomi Noda (Sayaka Kamiya) is the first to fire, shooting an Uzi at the people who were once her friends. When they return fire and Satomi dives for cover, she is shot. Hiding around the corner, she screams “it really hurts.”

This might be one of the most tragic moments in the film, and it takes place in one of the most drawn-out scenes of violence. Many of the deaths up until this point have been characterised by shock, with the killer not quite believing what they have done, and the victim seemingly painlessly dying. Their pain receptors unable to push through the shock of what is happening.

Satomi’s reaction to being shot shows how little these teenagers understand about their situation. None of them fully comprehend the consequences of hurting or killing another person. They are not inherently violent; they are just trying to survive. Her surprise belies an innocence that hasn’t quite been eroded. She is a girl who would not have hurt anyone were it not for the extreme provocation all of them find themselves under.

Instead of punishing the few who would willingly turn to violence, Battle Royale depicts an exaggerated version of these generational divides. They tar every young person with the same brush and create people desensitised to killing in the process of trying to deter others. It’s a flawed plan, built on stereotypes.

Director: Kinji Fukasaku

Writer: Kenta Fukasaku. Based on the novel of the same name by Koushun Takami

Starring: Tatsuya Fujiwara, Aki Maeda, Tarō Yamamoto, Chiaki Kuriyama, Kou Shibasaki, Masanobu Andō, Beat Takeshi