Spoilers for 28 Days Later (2002)

While Danny Boyle was not averse to horrific moments in his films – the baby on the ceiling in Trainspotting remains one of the most disturbing sequences put to film – until this year, 28 Days Later remained his only true horror movie.

Working with a script from Alex Garland, this take on the zombie film links to the rich history of undead cinema and would be credited with rejuvenating the genre, for better and worse. It’s also a socially conscious film, in a way that makes it stand apart from the films that came before, and much of the zombie cinema that came afterwards.

For many reasons, zombies have become the horror villains of choice for directors to make big statements. This isn’t always true – Lucio Fulci was happy to simply let the splatter fly, and the earliest examples were generally racist portrayals of voodoo – but you cannot look at George R. Romero’s Night of the Living of the Dead without seeing the blatant commentary on racism; or his sequel Dawn of the Dead without seeing the attacks on consumerism.

The Walking Dead and The Last of Us have used the genre to make similarly broad statements, highlighting the brutality of humans by sidelining the mindless hordes to create living antagonists that pose a much greater threat.

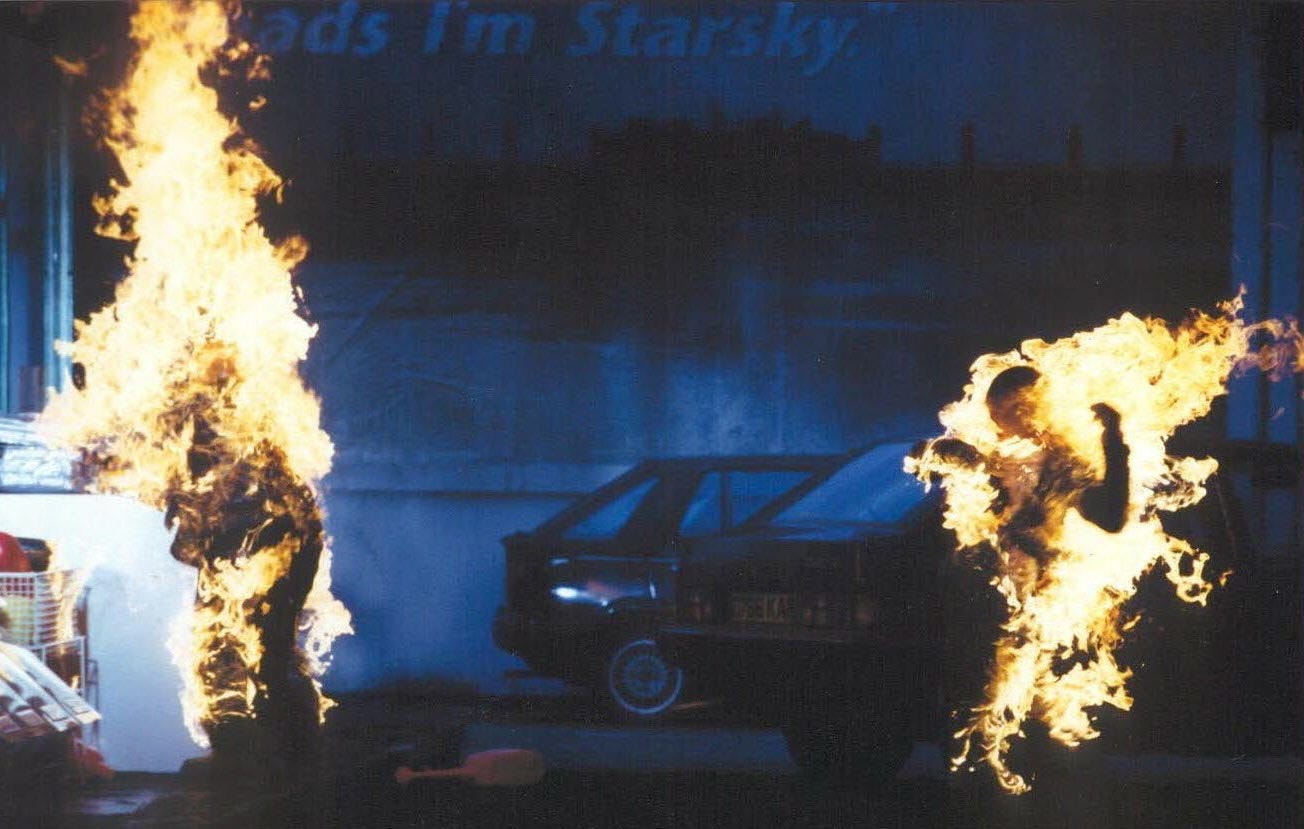

And 28 Days Later gets to this point. The frantic cat and mouse chase across the army base that makes up the final third of the film masterfully blurs the lines between heroes and villains, as each group brutalises the other in a bid to survive. Even when our group of protagonists, Jim (Cillian Murphy), Selena (Naomie Harris) and Hannah (Megan Burns), eventually escape, the film never completely loses that downbeat feeling.

Part of the reason for this is that Boyle and Garland do such a good job at the start of the film of pulling the audience out of their comfort zone, using the foundation that the Rage virus is only revealing man’s true nature.

This is highlighted in the prologue when animal liberation activists break into a facility to release a group of chimpanzees. We don’t see this straight away. Instead, we see news footage of various atrocities from across the world. Genocides. Murder. Rioting. In a Clockwork Orange-style twist, this is footage shown to the chimps to put them into a heightened state and activate the virus.

Before one person is bitten, the film tells us that we are the bad guys. This could have been done by highlighting the negative connotations around animal testing, but Boyle and Garland cleverly sidestep this issue. Instead, the animal liberation group are shown to be more violent than the mild-mannered scientist, who tries to warn them about the effects of releasing the chimps.

However, this base idea is mixed with tragedy when we get our first introduction to Jim. Waking from a coma to find the hospital abandoned, he heads out into the abandoned streets of London. By shutting off the busy thoroughfares of the capital for 45 minutes at a time, Boyle manages to create a ghost town, which is arguably the scariest part of the film. Anyone who has been to London understands that there isn’t a quiet part of the day. Whether it’s rush hour or 2am, there are always people about.

Completely oblivious to what has happened, we see Jim fall back on the things that meant something before the outbreak. He finds money left in the street and picks it up, his belief in the financial institutions still intact. The general belief is that if we have a little bit of money in our pocket, we can find a way out of a situation.

Similarly, after he meets Selena, he says that there still must be a government. Good or bad, it’s hard to imagine circumstances that would eliminate that level of power.

After finding the money, he seeks shelter in the church. In a short space of time, 28 Days Later takes through the three constants of power. Money, politics and faith. Three things that, whether we want them to or not, have a controlling impact on our lives. And in the church, we see a microcosm of what happened during the outbreak.

The nave of the church is closed, so Jim heads up the stairs walking past graffiti that exclaims:

“The end is very fucking nigh”

Already we can understand that people flocked to the church when the outbreak started. Likely, the religious first, and then the agnostic as people resorted to faith as a last hope. Lastly, the survivors came, not for redemption but for shelter, and having seen the devastation outside, they tagged the church with the cynical paint job.

When Jim looks out over the nave from above, he sees a mass of bodies and his first glimpse of the infected. They stand up, alert amongst the dead. In a series of very simple shots, Boyle communicates that three intrinsic parts of modern society are no longer useful to the populace. He has awoken in a world where money has no value; where politicians, indeed the very idea of politics and governing bodies at all, have disappeared; and one where faith – at a time where many would consider themselves agnostic or atheist – offers little more than momentary shelter before the end.

This is compounded when the priest is the first infected to attack Jim.

Director: Danny Boyle

Writer: Alex Garland

Starring: Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, Brendan Gleeson